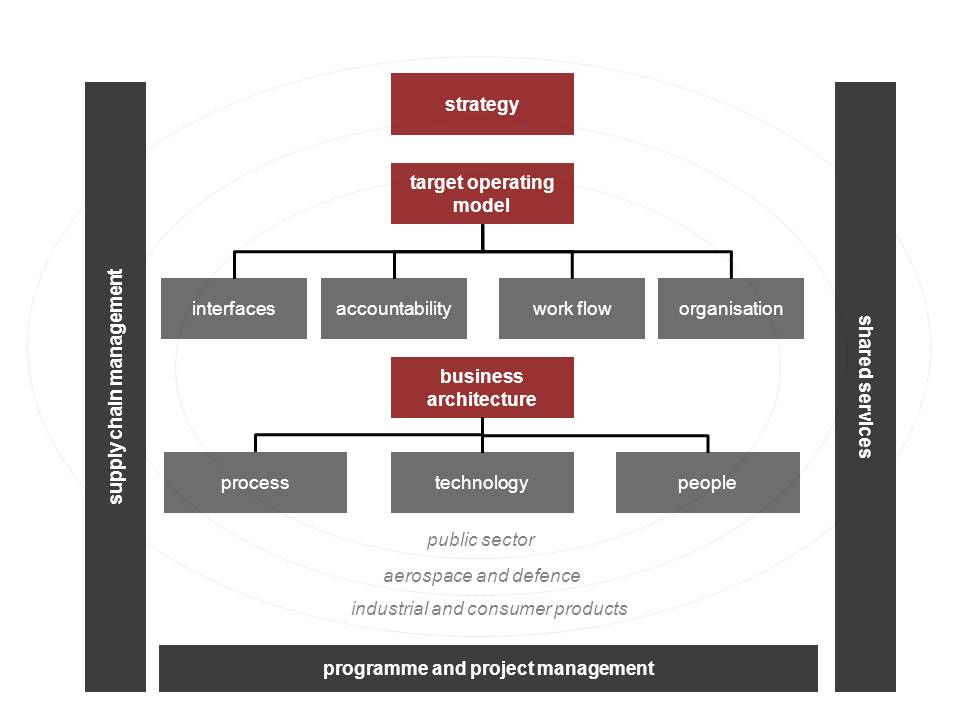

We developed this visual and have applied it many times. We like the top down representation of the principal activities. Defining the key accountabilities (from the outset) focuses minds and ensures alignment of how the work will get done.

Articles

Performance improvement in the supply chain

Supply chains – only strong leaders need apply!

An efficient supply chain can give customers a better choice of cheaper products and services. In many firms it now constitutes the main competitive advantage. But managers find that they have to review and improve it continually to adapt it to the needs and opportunities of the organisation. And it is also an expensive asset, responsible for 40-80% of the costs of the business. To manage it, strong leaders are required, who can challenge the practices of their peers. They must work out the best strategies and decisions to benefit the enterprise as a whole.

To quote Professor Yossi Sheffi of Massachusetts Institute of Technology:

‘Making stuff – that’s easy. Supply chain, now that is really hard.’

A symphony in many movements

Thomas Friedman* described the supply chain as a ‘symphony in many movements’, its major functions – ‘buy, make, move and support’ – combining in an unbroken and never-ending cycle, round the world and round the clock:

Buy: to procure the materials and components required for finished products and services

Make: to manufacture, produce and assemble products and services

Move: to store, warehouse and transport raw materials, stock and semi-finished and finished products and to fulfil orders

Support : to repair and return products.

Each function has specific objectives for cost, service, cycle time and quality. They depend on the operating constraints and opportunities that the aims and circumstances of the enterprise afford.

The supply chain can help to achieve competitive advantage, and specifically:

· to sustain performance that creates more value for shareholders

· to maintain the margins of products, despite severe pressure

· to re-define processes and structures to eliminate costs

· to harmonise systems and technologies to exploit synergies

· to establish collaborative relationships to support e-commerce

· to manage complexity in a network of businesses and achieve international consistency

· to generate transformational and iterative change

· to create a world-class image.

Common managerial challenges

Managing costs and optimising service disruptions to worldwide demand and supply can unbalance operations and devastate bottom lines. Structures that suit one business cycle may not suit the next.

During a cycle of growth, executives seek to promote that expansion. So they look for economies of scale, set the supply chain up to enhance service, and design structures to be flexible and scalable.

But during a downturn, the structure and costs of the supply chain offer an obvious place to seek savings. An under-used supply chain threatens profitability. Once priorities have been understood, risks must be assessed – and managed out. Even so, executives must be careful not to cause lasting damage to vital operations and customers’ satisfaction.

In a stable business, leaders need to exploit ways to optimise the supply chain – to balance the requirements of demand with the constraints of supply. This requires sound decisions, based on reliable data and robust analysis, to manage the costs of the supply chain and optimise service.

Restructuring the supply chain

The decision to restructure a supply chain can also spring from the need to:

· integrate a division or an acquired business, by merger and acquisition (M and A)

· restore profitability

· change the operating model in a fundamental way

· cope with significant changes in the market or business strategy

· prepare for eventual disinvestment.

These challenge the supply chain:

· consolidate volumes – but where and how?

· select new sources of supply and supply chain partners

· relocate sites and operations – particularly in foreign cultures

· re-shape the organisation

· change business processes – and reduce complexity

· set up controls to measure and report on performance and complement information systems

· set up constructive employee relations – to ensure a smooth transition.

Establishing supply chain partners, processes and structures

International trends – lower barriers for low-cost entrants, wider choice for customers, innovations in technology, and the environment – can all shorten the useful life of processes and structures. To stay competitive, companies must exploit these trends, often by developing more efficient, effective and robust processes, structures and partners. Procurement in lower-cost economies (in more distant and riskier spots) needs more sophisticated processes to plan and manage the supply chain. But it may not be necessary to revamp the whole structure. Carefully planned and executed initiatives can affect performance as profoundly as a major re-structuring.

Trends in the management of the supply chain

Every big firm wants to set up and run a world-beating supply chain. And globalisation has quickly exposed any failure to find new markets and economies of scale or to procure or manufacture at the lowest cost. The relentless pursuit of ‘more for less’ in each sector promotes new and better ways of operating. The effective management of the supply chain now tends:

· to reduce stocks of materials and finished goods and to improve service, reducing lead times and fulfilling orders more frequently. A leaner supply chain configured for service boosts the ability to supply ‘more for less’

· to cut cost, which makes outsourcing popular for selected functions in particular locations. The emergence of efficient providers in low-cost economies also propels functions – principally manufacturing and assembly – towards off-shoring

· to invest heavily – and to collaborate with other companies – in sales and operations planning (S and OP). Sectors such as Aerospace and Defence, with lots of locations and suppliers, find it hard to predict demand and manufacturing capacity. Poor data produce poor plans – with attendant delays, under-utilisation, on-costs and customers’ dissatisfaction

· to form consortia with other companies (usually non-competitors operating overseas) to procure consolidated services at lower unit cost

· to analyse risks and shape contingencies. Urgency, the removal of surplus capacity, the consolidation of volumes, and globalisation put the supply chain at greater risk. One failure in the tightly balanced system could lead to catastrophe. So big firms must know how to gauge risks and draw up contingencies

· to exploit advances in information technology, achieve carbon-neutral status and form huge, multi-mode distribution companies.

A framework for improving the supply chain

A framework for improving a supply chain has four integrated stages: strategy; operating model; processes and systems; and organisational structure.

· Strategy for the supply chain – a rigorous analysis of the external environment, market dynamics and organisational capabilities results in a clear statement of what the supply chain can be expected to achieve and to cost and of how it should operate in the markets and locations served, give competitive advantage and maximise value for shareholders.

· Operating model – defining an operating model to realise the strategy demands the generation, evaluation and selection of options, resulting in a clear statement of how the supply chain will operate and an overview of the partners, processes and structures required. On completion of this process, the organisation will have clearly understood the options and the rationale for preferring one to another, and will have selected the most desirable operating model.

· Processes and systems – the discipline of defining the appropriate processes and systems shows how new capabilities will be applied and how they will operate. A supply chain allows many interactions (and mergers of data) between its internal and external partners. It will also result in a business case and plan for implementation to show when and how the targeted value can be obtained.

· Organisational structure – the structure must complement the operating model, the roles of partners and the emerging infrastructure of processes and systems. It will define how new capabilities will be implemented and how people, processes and systems will interact.

The framework shows the four desirable attributes of a supply chain: it should be aligned, affordable, accountable and agile. Each quality can be found at the interface between two of the stages.

· Aligned – the operating model must be aligned with the strategy for the supply chain. Lack of alignment will impair the implementation of the overall business strategy.

· Affordable – the processes and systems need to be affordable. Too ambitious or sophisticated a method of planning and executing the operating model will burden the business with unnecessary costs.

· Accountable – clear accountabilities and responsibilities should be set for all the parts of the supply chain. Great care must be taken to communicate effectively and define all roles and responsibilities.

· Agile – the organisation should be agile (scaleable and flexible) and able to accommodate changes in the strategy.

Strategy for the supply chain

Problems and causes – at an early stage a series of assessments should define the organisation’s strategic problem(s) and their causes – any lack of capacity, capability or performance threatening the growth or survival of the company.

Opportunities and constraints – this will reveal which opportunities in the supply chain have the most potential to increase value: perhaps to manufacture in low-cost markets; to consolidate logistics at hubs; or to contract out major parts of the supply chain.

The objectives, strategies, policies and requirements of the centre and of the business units – the strategy for the supply chain will necessarily be closely linked to the plans for the corporate centre and the business units. Collaboration on customers, supply and value will heavily influence the strategy.

Products, markets and customer segments – a supply chain has a major influence on whether and how an organisation should sell new products in new markets. For example, low-cost supply may offer lucrative margins, but the infrastructure for manufacturing and logistics may be of low quality, increasing risk.

Available capabilities and resources – the organisation will evaluate its operational and organisational capabilities and either spot gaps that require improvement or temper the strategy to the constraints.

Expectations on performance and cost – the service (e.g. lead times and frequencies) required by internal and external customers will influence cost. An optimal position has to be determined.

Case for change – a clear statement – what will change, why it will be worth it and how it will be done – in qualitative and financial terms.

Channels of supply and distribution – this states how the organisation’s products get to the customer. It will show where a change in ownership occurs. For example, an organisation could sell its products directly to customers, and manage the entire supply chain itself. Many choose to manage a network of country-based manufacturers wholesalers and distributors until volume has been built up in a new market.

Business problems and causes – reasons for failure in a supply chain can be very complex. They range from small deficiencies in each function – such as a lack of alignment with objectives – to a major problem with a particular function – such as the quality of manufacturing. The root cause must be found before any change can be made. The following table matches problems to causes, showing how the customer’s difficulties spring from the supply chain. It results in a clear statement of what capabilities need to improve. Similar exercises should be done for all the known trouble spots in the supply chain.

Operating model

Operational problems and causes – an early stage will consist of a series of assessments that examine the organisation’s operational problems and confirm their nature and causes. These will be related to some (or many) of the challenges mentioned earlier.

Customers’ (service) requirements – each major function in the supply chain has service level requirements. Some – procurement, manufacturing, logistics and support – have distinct needs. Each one looks to its internal customer to provide a defined performance typically related to responsiveness (such as lead time to fulfil an order and the frequency of order fulfilment). It also involves so-called ‘added value’ services, the supplier undertaking to do some aspects of its customer’s work (for example, a distribution company may pick, pack and label shipments, as well as deliver them). Requirements will vary by product and customer segment.

Scope – a clear statement of the functional and geographical boundaries of the supply chain. Higher-level statements can be set earlier on, but a detailed knowledge of the strategy itself and of the customer’s requirements will produce a detailed statement on which to base specific improvements in the supply chain.

Operating policies – these state the policies and rules to be implemented or observed by each function (for example, procurement shall be with end suppliers and not agents; manufacturing shall contract out the assembly of the final product; logistics shall ship full loads, using the lowest-cost carriers).

Integrated process model – this states the primary (or common business) processes for the organisation and how they integrate. The processes embody the rules, activities, responsibilities, structures, forums and systems necessary to co-ordinate and align decisions and action. Though easily said, this poses the most complex of challenges for an organisation.

Capabilities and resources – these will be a product of the operating model and the processes in the supply chain. Gap analysis will indicate whether the mix of capabilities and resources seems appropriate. An inappropriate mix will be resolved by adding (or reducing) internal or external capabilities and resources.

Roles and responsibilities – the processes will be mapped against each supply chain partner to confirm their several obligations. A number of charts (e.g. one for each business function) will be produced to state who should be responsible, accountable, consulted or informed (RACI) for each process (and sub-process).

Physical supply chain network – this will state the major nodes and flows in the supply chain. It will result from extensive ‘flow path’ modelling to optimise the costs and service within the constraints set by the requirements for service.

Processes and systems

Functional requirements – these may be data or features of the process or system necessary for the effective management of activities. They may assist the execution of orders or decisions and could be the inputs or outputs necessary for activities (for example, purchase orders should state specific codes; manufacturing schedules should ‘roll up’ from daily to weekly views; customs paperwork should be electronically attached to customers’ orders et cetera).

Supply chain processes – these show the processes that span business functions (such as those for managing purchase orders, production, inventory, sales orders and fulfilment, and finance). A process describes in detail how operations will be planned. This will build on the integrated process model developed in the previous stage. Planning happens on many levels in an organisation – from strategy to execution. Each operations plan created by a business function triggers decisions throughout the organisation. Unaligned decisions (in functions or timescales) can be costly and difficult to reverse. Operations planning states how processes shall be integrated to encompass a more effective and efficient translation of true demand for the corresponding products and services.

Activities and tasks – the events that comprise a process, named, described and associated with other events (such as dependencies and interfaces) may be broken down into specific (transactional) tasks (for example, raise purchase order, determine capacities at manufacturing plants, report cost variances – all supply chain activities).

Measures of performance – a balanced scorecard will present the appropriate financial and operational measures. This should support rapid insights and enhance decision-making. It will help the supply chain focus on the objectives it has been set, while providing access to the right information at the right levels within the organisation.

Information systems – these, a fundamental requirement in any supply chain, can be configured at enterprise level (enterprise resource planning systems such as SAP or Oracle) or at individual plants and logistics sites (manufacturing or logistics systems). Integration, a complex exercise, configures and joins up systems to produce the required outcomes and present a seamless experience for the users.

Skills – the skills required to manage the processes, activities and tasks, sub-divided into pure skills (for example, the ability to use systems and manage an activity or function), knowledge (for example, supply markets in Asia) and competences (for example, leadership).

Organisational structure

Organisational policies – this will state which parts of the organisation should be responsible for the functions of the supply chain. For example, it may be a matrix model for the supply chain – one business unit (BU) may manage buying on behalf of all BUs, or may control all manufacturing plants in the organisation, or could provide a corporate logistics service for the whole organisation. Alternatively the policy might be for each BU to have an independent supply chain. Corporate strategy has a heavy influence.

Organisational design and structure – translates the operating model into tangible results; to manage assets, control resources and create wealth. It provides a framework in which people can excel and contribute positively to the success of the supply chain. It should have the ability to renew itself and to adapt to emerging situations and changing circumstances. The structure of the supply chain also has a major influence on costs and competiveness.

Roles and jobs – the processes and activities will determine the necessary roles and the managerial accountabilities and responsibilities, combined in fully specified jobs.

Managerial controls – these will be defined to monitor performance and prompt the right managerial behaviour (for example, buying authorisation levels, inventory controls and cycles of review meetings.

Performance management – the ability to manage performance equips an organisation to organise the supply chain, control costs, mitigate risk and find innovative ways to improve its effectiveness. Efforts to manage performance more effectively will involve changes to metrics, reporting, methods of analysis, planning, budgeting and forecasting.

People and recruitment – people in the organisation will be given specific jobs. Any gaps in capabilities and resources could be resolved by a programme of recruitment (for example, of people with experience of new supply markets, manufacturing in new countries or expertise in managing complex freight shipments) or training.

Training – a training programme may focus on developing skills, knowledge and competences (in, for example, systems, business functions or management).

Approach

A programme to improve the supply chain should proceed via stage gates, signing off specific elements of the design before going on to the next stage. The adopted methodology could be whatever the organisation is accustomed to, or one recognised; for example by The Office of Government Commerce (for example, PRINCE, Managing Successful Programmes).

About the Author

Callum is a director of Moy and Company Ltd, which is a business and IT transformation consultancy that specialises in helping clients improve their performance.

Callum has over thirty years’ experience of managing business improvement in the private and public sectors for both small and large organisations. He leads work that encompasses operating strategy, target operating model, process and organisational design, IT infrastructure and business applications and outsourcing.

Contact Callum to share your thoughts or to ask about how to improve business performance.